On March 31, 2014, the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Health Insurance Marketplace officially closed for most people until open enrollment begins for 2015 health plans on November 15, 2014. By the end of the first open enrollment period, 272,539 Michigan residents had signed up for a plan through the ACA marketplace. Assuming that many of these residents complete the enrollment process, Michigan marketplace enrollment exceeded 2014 projections from CHRT, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Urban Institute.

This issue brief summarizes the plans that have been offered on the ACA individual marketplace, explains the financial assistance available through the marketplace, describes the operational challenges faced by the marketplace, and recaps Michigan’s enrollment during the 2014 open enrollment period.

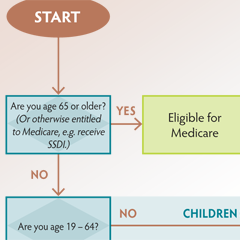

The first marketplace open enrollment period began on October 1, 2013, and ended on March 31, 2014. The marketplace offered consumers the opportunity to compare qualified health plans (QHPs) from multiple insurers. QHPs were required to comply with several newly effective ACA provisions which created minimum standards for coverage, regulated the design of plans, and allowed premiums to vary based on a limited set of factors unrelated to health status. To make QHPs more affordable to consumers, the ACA provides tax credits and cost-sharing reductions to qualifying individuals to lower the premium and out-of-pocket costs.

Suggested citation: Fangmeier, Josh; Hatch-Vallier, Leah; and Udow-Phillips, Marianne. Michigan Health Insurance Marketplace: Overview and Operations Issue Brief. August 2014. Center for Healthcare Research & Transformation, Ann Arbor, MI.

Special thanks to Jon Linder.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) expands health insurance coverage to millions of uninsured Americans and introduces several reforms to the health insurance market, particularly for people who purchase coverage on their own or receive it through employment at a small business. These reforms standardize benefits, limit insurance rating practices, prohibit coverage denials, limit out-of-pocket costs, and levy new taxes on health plans. These reforms primarily apply to non-grandfathered qualified health plans, sold on and off the marketplace, beginning in 2014. Combined with other ACA provisions already in effect, these reforms mean that some people in the individual and small group insurance markets looking for coverage on the new health insurance marketplaces will experience significant increases in premium costs for coverage and others will experience significant reductions.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) expands health insurance coverage to millions of uninsured Americans and introduces several reforms to the health insurance market, particularly for people who purchase coverage on their own or receive it through employment at a small business. These reforms standardize benefits, limit insurance rating practices, prohibit coverage denials, limit out-of-pocket costs, and levy new taxes on health plans. These reforms primarily apply to non-grandfathered qualified health plans, sold on and off the marketplace, beginning in 2014. Combined with other ACA provisions already in effect, these reforms mean that some people in the individual and small group insurance markets looking for coverage on the new health insurance marketplaces will experience significant increases in premium costs for coverage and others will experience significant reductions.

One in five Michigan residents report having been diagnosed with depression at some point in their lives. Mental health disorders cause more disability among Americans than any other illness group.

One in five Michigan residents report having been diagnosed with depression at some point in their lives. Mental health disorders cause more disability among Americans than any other illness group.

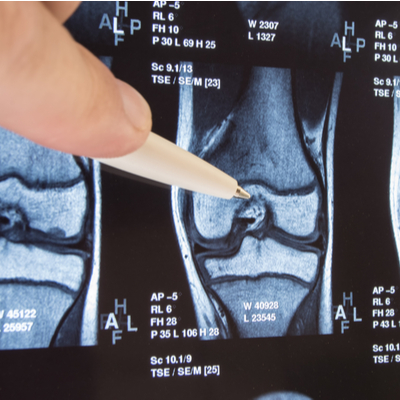

Understanding the impact of health care coverage (or the lack of it) on health care access is crucial to improving health care in Michigan.

Understanding the impact of health care coverage (or the lack of it) on health care access is crucial to improving health care in Michigan.